Metcalfe’s Law Applied to Certification Marks

Foundational Concepts: Understanding Metcalfe’s Law and Network Effects

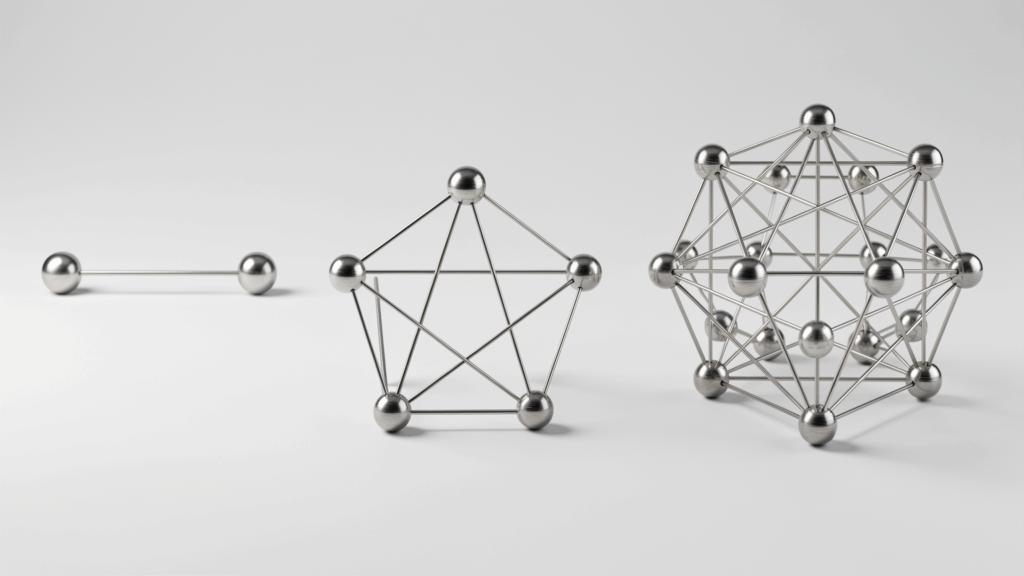

Metcalfe’s Law, formulated by Robert Metcalfe, co-inventor of Ethernet, posits that the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users [1]. This fundamental principle has become central to understanding digital platform economics and network-based business models. The law suggests that as a network grows, its utility and value increase exponentially rather than linearly—each new participant adds value not only to themselves but to all existing participants [2].

The mathematical elegance of Metcalfe’s Law lies in its implication that network value scales with n², where n represents the number of network participants. However, research has demonstrated that this relationship may not always hold perfectly across all contexts. Recent validation studies using Meta and Netflix data from 2011 to 2020 show that Metcalfe’s law continues to demonstrate considerable explanatory power for modern digital platforms, despite variations in their revenue models, user acquisition strategies, and technological infrastructure [1].

Network Effects in Digital Ecosystems

Network effects represent the phenomenon where the value of a product or service to existing users increases as more users join the network [3]. These effects can be categorized into same-side network effects (where additional users on the same side of the market create value) and cross-side network effects (where additional users on one side create value for users on the other side) [4]. In the context of certification marks, cross-side network effects are particularly relevant, as certified products benefit consumers seeking assurance, while producers benefit from increased consumer demand for certified goods.

The strength of network effects varies significantly depending on market context and user heterogeneity. Research on two-sided markets demonstrates that both the same-side network externality and search costs impact platform strategies monotonously, but these effects are not always consistent across different pricing and revenue models [5]. Understanding these dynamics is critical for analyzing how certification networks create and capture value.

Limitations and Extensions of Metcalfe’s Law

While Metcalfe’s Law provides powerful intuition, empirical evidence suggests its applicability varies by context. Studies employing log-linear and log-quadratic specifications reveal that cryptocurrency networks often exhibit sublinear relationships with n rather than purely n² relationships, particularly in short-term scenarios [6]. Additionally, emerging frameworks like Reed’s Law and Sarnoff’s Law offer alternative perspectives: Sarnoff’s Law (v ∝ n) applies to broadcast networks where value scales linearly, while Reed’s Law (v ∝ 2^n) suggests exponential value creation through group formation [7].

Recent scholarship introduces the “sublinear knowledge law,” demonstrating that knowledge growth is notably slower than both the growth rate of network size and the rates outlined by traditional laws like Metcalfe’s [7]. This nuance is particularly important when considering certification networks, where the informational component of certification may not scale quadratically with network size due to information saturation and market knowledge limitations.

Certification Marks as Quality Signals and Trust Mechanisms

Definition and Function of Certification Marks

Certification marks represent formal assurances that products or services meet specific standards established by third parties [8]. They function as credence attributes—quality characteristics that cannot be assessed by consumers at the point of sale without additional information [8]. In the context of diet-specific certifications like Certified Paleo or Keto Certified, these marks communicate compliance with specific dietary formulations and ingredient restrictions that would be impossible for consumers to verify independently.

The system of food credence attributes involves multiple stakeholders with distinct motivations: retailers and processors seeking to establish trust, NGOs and government authorities setting standards, and consumers attempting to access reliable product information [8]. Certification marks bridge the information asymmetry gap between producers (who possess complete knowledge about formulation) and consumers (who lack detailed product information). This informational role is foundational to the value proposition of certification networks.

Consumer Trust and Premium Pricing

Empirical research across diverse food categories demonstrates that certification marks significantly influence consumer purchase intentions and willingness to pay premiums. In organic food markets, perceived brand authenticity mediates the relationship between product qualities and consumer trust, with consumers willing to pay substantial premiums for products carrying recognized certifications [9]. The mediation pathway—Brand Authenticity → Experiential Quality → Consumer Trust → Purchase Intention—shows how certification integrates into broader consumer decision-making frameworks.

Trust in certification systems proves particularly powerful in culturally specific contexts. Research on organic food certification reveals that cultural value orientation moderates the relationship between perceived value and trust in certification, with stronger effects observed in collectivistic cultural contexts [10]. Similarly, in halal-certified food markets, consumer trust in the certifying institution demonstrates the highest correlation with loyalty, even when consumers lack a detailed understanding of certification standards and processes [11]. This suggests that the certification mark itself becomes a symbolic representation of trustworthiness that often supersedes detailed technical knowledge.

Information Asymmetry Reduction

Certification marks address information asymmetry through multiple mechanisms. Most directly, they serve as signals of product quality and compliance, reducing the perceived risk associated with product purchases [12]. The signaling function of third-party certifications proves particularly effective in reducing financing costs in financial markets, with empirical evidence from green bond markets showing that third-party green certification significantly reduces borrowing costs by mitigating information asymmetry [13].

However, the effectiveness of certification signals depends critically on consumer understanding and trust in the certifying body. Research on halal certification demonstrates that when certification credibility is high and brand transparency is maintained, trust mediates the link between certification status and purchase intention [14]. Conversely, proliferation of competing or unreliable certification marks can lead to consumer skepticism, with the “rotkäppchen effect” describing how sector-scale proliferation of certification programs creates mimicry dynamics where unreliable labels dupe consumers into ignoring all signals in a category [15].

Network Effects in Two-Sided Markets and Platforms

Platform Architecture and Cross-Side Network Effects

Certification mark systems function as two-sided platforms, connecting certified product providers with consumers seeking assurance. Unlike simple information networks, certification platforms exhibit strong cross-side network effects: the value to consumers increases as more producers adopt certification (expanding choice), while the value to producers increases as more consumers recognize and reward certification (expanding addressable market) [4].

The magnitude of cross-side network effects depends on product-market characteristics and consumer preferences. Research on dual-sided mobility platforms demonstrates that the platform’s commission rate, member participation patterns, and prior user experiences jointly shape equilibrium dynamics [16]. For certification networks, analogous factors include the stringency of certification standards, the visibility of certified products in retail channels, and the cumulative consumer experience with certified products over time.

User Participation and Market Dynamics

Cross-period network effects contribute significantly to user stickiness and platform sustainability. On two-sided platforms, same-side network effects (where additional producers or consumers on one side enhance value for existing producers or consumers) contribute to user stickiness by improving product learning and experience [4]. For certification networks, this translates into producer retention (as certified producers benefit from growing consumer awareness) and consumer commitment (as certified products become more familiar and accessible).

However, platforms face critical threshold dynamics. The rise-and-fall patterns in two-sided markets follow S-shaped learning curves, influenced by marketing efforts, word-of-mouth effects, and cumulative consumer experience [17]. Certification networks similarly depend on achieving critical mass—sufficient adoption by both producers and consumers to create self-reinforcing growth. Once critical mass is achieved, network effects accelerate growth; conversely, below critical mass, networks may languish or collapse.

Quality Regulation and Competitive Dynamics

In two-sided markets with heterogeneous providers, platforms adopt quality regulation strategies to maintain system integrity. Research on competing platforms demonstrates two primary approaches: the exclusion strategy (denying market access to low-quality providers) and the subsidization strategy (providing incentives for high-quality participation) [18]. Certification networks inherently adopt exclusion strategies through their standards-setting mechanisms, denying certification to non-compliant producers.

When multiple certification standards compete (as in the contemporary landscape with numerous diet-specific certifications), equilibrium outcomes depend on standard stringency and consumer preferences. Research on competing platform standards shows that asymmetric quality regulation modes (where different platforms adopt different strategies) do not necessarily produce moderate outcomes for market participants [18]. This suggests that certification market consolidation or fragmentation outcomes are not predetermined but emerge from the specific strategic choices of competing certification organizations.

Application to Food Certification Systems and Consumer Markets

Dietary Certification Mark Expansion

The proliferation of dietary certification marks—including Certified Paleo, Keto Certified, Whole30 Approved, Vegan, Gluten-Free, and numerous others—creates a multi-network certification ecosystem. Each certification network represents a distinct two-sided market with its own producer and consumer bases. The value of each network depends on both the number and “quality” (in terms of purchasing power and loyalty) of its participants.

Food certification systems serve both informational and commercial purposes. While formal certifications like Halal and Kosher emerged primarily for religious or health compliance, contemporary diet-specific certifications increasingly serve as commercial branding and differentiation mechanisms [19]. The commercialization of halal certification in Indonesia illustrates how certification has shifted “from a religious safeguard to an economic commodity,” with certification consultants, fee structures, and fast-track services creating incentive structures that influence adoption patterns [19].

Consumer Willingness to Pay for Certified Products

Empirical research consistently demonstrates that consumers exhibit substantial willingness to pay (WTP) premiums for certified products. Meta-analysis across numerous food categories shows premium rates for certified products often exceed 100%, with particularly high premiums for organic and green certifications [20]. Research on rice certification in China found that consumers prioritize taste and nutritional quality, but combining these attributes with recognized certification labels—particularly green certification alongside well-known brands—significantly elevates preference levels [20].

However, the premium acceptance varies substantially based on consumer characteristics, product categories, and certification type. Younger, more educated consumers show stronger preference for and willingness to pay for certified products, particularly when combined with digital traceability features [9]. Additionally, consumer skepticism represents a significant constraint on premium pricing, with studies showing that consumer doubt about certification authenticity negatively impacts perceived value [21]. This suggests that certification networks must continuously invest in credibility maintenance to sustain premium pricing power.

Certification Networks and Value Chain Integration

Certification networks create value by integrating previously fragmented value chains. Short food supply chains (SFSCs) that emphasize local producers, transparency, and direct consumer connections increasingly incorporate certification systems to scale trust beyond personal relationships [22]. Combining producer branding, certification, traceability systems, and community engagement creates “hybrid governance,” in which relational trust (based on personal knowledge) and formal assurance (based on third-party verification) reinforce each other [23].

Research on geographical indication (GI) branding combined with producer organizations demonstrates how certification networks enable smallholder farmers to access premium markets and build collective reputation [24]. The integration of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) with GI certification creates network effects where individual producers benefit from collective brand reputation while simultaneously contributing to it. This dynamic represents a concrete application of Metcalfe’s Law dynamics—each additional certified producer increases network value for all participants.

Metcalfe’s Law Applied to Certification Mark Networks

Network Value Creation in Certification Ecosystems

Applying Metcalfe’s Law to certification mark networks requires recognizing that certification value emerges from both production-side and consumption-side networks. The value function for a certification network can be conceptualized as V = k(P × C), where P represents the number of certified producers and C represents the number of consumers recognizing and valuing the certification, with k representing the average transaction value [25]. This formulation suggests that value creation depends on achieving balanced growth on both network sides.

However, certification networks demonstrate important deviations from pure quadratic scaling. Unlike undifferentiated communication networks, certification networks involve quality filtering: not all producers gain equal value from participation, and not all consumers derive equal utility from certification. A high-quality producer in a certification network derives greater value from each additional consumer than does a low-quality producer, suggesting that certification network value scales super-linearly with consumer participation but sub-linearly with producer participation, creating incentives for quality concentration.

Value Accumulation and Lock-In Effects

As certification networks grow, several mechanisms generate lock-in effects that amplify network value beyond quadratic growth rates. First, standardization effects: as a certification mark becomes dominant within a category, retailers and distributors preferentially stock certified products, creating barrier effects that disadvantage non-certified competitors [26]. Second, information familiarity: as consumers accumulate experience with a certification mark, the information processing cost of certification recognition declines, increasing the effective value of participation [4].

Third, brand spillover: successful certification networks develop brand equity that extends beyond individual product transactions. Research on halal branding demonstrates how investment in certification credibility, community engagement, and transparency creates long-term brand loyalty that transcends specific product attributes [27]. This suggests that mature certification networks capture value not merely from current transactions but from accumulated brand equity that influences future purchasing behavior.

The mediating role of perceived brand quality in certification networks proves particularly important. Studies show that halal labels and certification have significant influence on purchase intentions both directly and indirectly through perceived brand quality, with perceived quality showing a mediating effect that amplifies the certification-to-purchase relationship [28]. This indicates that certification network value includes quality-signaling benefits that operate through brand-perception channels rather than purely through information channels.

Network Effects and Market Concentration

Certification networks demonstrate strong tendencies toward market concentration and winner-take-all outcomes when cross-side network effects are strong [4]. However, product heterogeneity and consumer preference heterogeneity can sustain multiple competing certification networks. Research on multi-homing (where agents participate in multiple networks simultaneously) shows that when consumers actively use multiple competing certifications, market outcomes become less concentrated [29].

The dynamics differ significantly between categories with homogeneous consumer preferences and those with fragmented preferences. High-value dietary certifications that appeal to specific communities (paleo, keto, gluten-free) may sustain multiple competing networks simultaneously by each capturing distinct consumer segments. This pattern contrasts with universal certifications (organic, fair-trade) that aspire to mainstream adoption and therefore face stronger winner-take-all pressures.

Strategic coalition formation among certification networks can alter competitive dynamics. Research on cross-market platform cooperation demonstrates that joint membership systems allowing consumers to benefit from participation across multiple platforms can achieve efficiency gains while reducing winner-take-all dynamics [30]. Similarly, certification networks could theoretically coordinate through mutual recognition agreements, though current market structures emphasize competitive differentiation rather than cooperation.

Implications, Challenges, and Future Research Directions

Regulatory and Policy Considerations

The application of Metcalfe’s Law to certification networks carries important regulatory implications. As certification networks achieve market dominance through network effects rather than superior efficiency, antitrust and consumer protection authorities must consider whether network effects create problematic market power [31]. The challenge intensifies because the most valuable certification networks are those that successfully exclude non-compliant producers, creating barrier effects that simultaneously protect consumer interests and restrict competition.

Policy frameworks addressing market power in two-sided platforms emphasize the importance of considering specific market conditions rather than applying uniform rules. Research suggests that network effects’ competitiveness implications depend on factors including market size, consumer affiliation patterns, and the stringency of quality standards [18]. For certification networks, this implies that regulatory approaches might distinguish between monopolistic certifications (like Halal certification in predominantly Muslim markets) and competitive certifications (where multiple recognized alternatives exist).

Challenges in Certification Network Sustainability

Despite network effect potential, certification networks face persistent challenges in achieving stable sustainable value capture. First, information saturation: as consumer awareness of certification increases, the informational value of certification marks declines unless certification organizations continuously innovate in communication and differentiation [32]. Second, commodification risks: certification marks can lose distinctiveness through overuse or weakening of standards, with research on halal certification showing commercialization pressures that may erode spiritual and substantive integrity [19].

Third, verification credibility: as certification networks grow and diversify, maintaining credible, consistent verification standards becomes increasingly challenging. The rise of third-party certification providers creates agency conflicts where profit-maximizing incentives might conflict with certification stringency [8]. Consumer awareness of these dynamics feeds skepticism that dampens premium pricing power.

Future Research Directions

Several research gaps merit attention. First, empirical quantification of network effects in specific certification categories remains limited. While theoretical frameworks predict quadratic or near-quadratic relationships, empirical validation in food certification categories is sparse. Longitudinal studies tracking producer and consumer participation growth in specific certifications could yield evidence about actual scaling dynamics.

Second, the comparative analysis of competing certification networks within single product categories requires development. How do consumers allocate attention across multiple certifications? Under what conditions do certification networks achieve coexistence versus winner-take-all outcomes? Third, the role of digital technologies in augmenting certification network effects deserves investigation. Blockchain-based transparency systems, QR code verification, and real-time traceability platforms may enable certification networks to scale beyond historical limitations, potentially achieving stronger network effects than traditional certification marks.

Fourth, cross-cultural variation in network effect dynamics in certification systems warrants attention. Preliminary evidence suggests that cultural factors influence how consumers weigh certification relative to other purchasing cues, but systematic comparative analysis remains underdeveloped. Finally, the intersection between certification network effects and sustainability deserves investigation—do certification networks that achieve greater scale necessarily produce more positive sustainability outcomes, or can network effects primarily benefit incumbent producers?

Conclusion

Metcalfe’s Law provides a powerful conceptual framework for understanding value creation in certification mark networks, but certification systems deviate from pure network value functions in important ways. The value of certification networks depends critically on balanced growth of both producer and consumer sides, quality maintenance that prevents commodification, and preservation of verification credibility. Successful certification networks like Halal, Fair Trade, and emerging diet-specific certifications demonstrate that when these conditions are met, network effects can amplify substantially through standardization, brand equity, and lock-in mechanisms. However, competitive pressures and commodification risks create ongoing challenges to network value sustainability. Future research should empirically quantify actual network effects in specific certification categories, investigate mechanisms of coexistence among competing certifications, and explore how digital innovations might augment traditional network effect dynamics in certification systems.

References

[1] A. Bekh, “METCALFES LAW IN THE DIGITAL MEDIA MARKET,” Vsnik Marupolskogo deravnogo unversitetu. Ser: Ekonomka, 2021, doi: 10.34079/2226-2822-2021-11-22-68-72.

[2] J. Wilbanks, “We need a Web for data,” Learned Publishing, Oct. 2010, doi: 10.1087/20100410.

[3] H. Verby, “Network effects in Facebook,” None, Jun. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/3234781.3234782.

[4] Z. Zhou, L. Zhang, and M. W. V. Alstyne, “How Users Drive Value in Two-Sided Markets: Platform Designs That Matter,” MIS Q., Mar. 2024, doi: 10.25300/misq/2023/17012.

[5] D. Zhao, S. Yang, Z. Yuan, and J. Hao, “Payment Method Strategy Selection for Production-Capacity-Sharing Platform: Whether to Provide Online Payment Methods for Two-Sided Users,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.3390/jtaer21010005.

[6] A. Ginavar, A.-I. Conda, D. Pele, M. Mazurencu-Marinescu-Pele, and D. Manea, “Cryptocurrency Market Analysis: Insights from Metcalfes Law and Log-Periodic Power Laws,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, Jul. 2025, doi: 10.2478/picbe-2025-0040.

[7] X. Wang, L. Fu, H. Kang, Z. Jin, L. Zhou, and C. Zhou, “Revisiting Network Value: Sublinear Knowledge Law,” arXiv.org, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2304.14084.

[8] S. P, Z. A, L. B, R. K, and I. A, “Food Credence Attributes: A Conceptual Framework of Supply Chain Stakeholders, Their Motives, and Mechanisms to Address Information Asymmetry.,” Jan. 2023, doi: 10.3390/foods12030538.

[9] X. Liu, X. Qiao, Y. Chen, and M. Chen, “The Dilemma of the Sustainable Development of Agricultural Product Brands and the Construction of Trust: An Empirical Study Based on Consumer Psychological Mechanisms,” Sustainability, Oct. 2025, doi: 10.3390/su17209029.

[10] T. N. Bui, “Price Premium Acceptance for Organic Food: A Behavioral Economics Analysis of Consumer Decision-Making in Vietnam’’s Emerging Market,” Journal of economics, finance and management studies, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.47191/jefms/v8-i2-41.

[11] A. Madun, Y. Kamarulzaman, and N. Abdullah, “THE MEDIATING ROLE OF CONSUMER SATISFACTION IN ENHANCING LOYALTY TOWARDS MALAYSIAN HALAL-CERTIFIED FOOD AND BEVERAGES,” Online Jurnal of Islamic Management and Finance, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.22452/ojimf.vol2no1.1.

[12] W.-P. Wu, A. Zhang, R. V. V. Klinken, P. Schrobback, and J. Muller, “Consumer Trust in Food and the Food System: A Critical Review,” Foods, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.3390/foods10102490.

[13] R. Wang, “An Empirical Analysis of Pricing Determinants in Chinas Green Bond Market: A Study on Risk Mitigation Effects Through Certification Signals, Rating Analysis, and Disclosure Quality,” International Journal of Global Economics and Management, Aug. 2025, doi: 10.62051/ijgem.v8n1.26.

[14] B. Fujitha, T. W. Nugroho, and D. Suminar, “Halal Certification as a Trust Signal in Muslim Consumers Purchase Intentions for Boocha Booms KombuchaD,” Poster conference proceeding the International Halal Science and Technology Conference 2025 (IHSATEC): 18th Halal Science Industry and Business (HASIB), Dec. 2025, doi: 10.31098/hst25111.

[15] R. Buckley, “Sector-Scale Proliferation of CSR Quality Label Programs via Mimicry: The Rotkppchen Effect,” Sustainability, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.3390/su151410910.

[16] F. Ghasemi, S. H. Tabatabaei, S. Ghanadbashi, R. Kucharski, and F. Golpayegani, “Reinforcement Learning Approach for Improving Platform Performance in Two-Sided Mobility Markets,” 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1109/ITSC58415.2024.10919911.

[17] F. Ghasemi and R. Kucharski, “Modelling the Rise and Fall of Two-sided Markets,” Adaptive Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, May 2024, doi: 10.5555/3635637.3662920.

[18] G. Lyu, L. Tian, and W. Wang, “EXPRESS: Exclusion or Subsidization? A Competitive Analysis of Quality Regulation Strategy for Two-sided Platforms,” Production and operations management, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1177/10591478231224915.

[19] M. Muhaimin, “THE COMMERCIALIZATION OF HALAL CERTIFICATION IN INDONESIA’’S FOOD INDUSTRY,” Journal of Islamic Tourism Halal Food Islamic Traveling and Creative Economy, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.21274/ar-rehla.v5i2.11534.

[20] P. Fang, Z. Zhou, H. Wang, and L. Zhang, “Consumer Preference and Willingness to Pay for Rice Attributes in China: Results of a Choice Experiment,” Foods, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.3390/foods13172774.

[21] B. Cicci and L. J. D. M. Carmona, “The impact of consumer skepticism on perceived value and purchase intention of organic food,” Revista de Administrao da UFSM, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.5902/1983465985505.

[22] N. Shevchenko and O. Demianenko, “THE ROLE OF LOCAL PRODUCERS BRANDING IN BUILDING CONSUMER TRUST WITHIN SHORT FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS,” Economic scope, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.30838/ep.207.276-282.

[23] E. C. D. C. Walger, T. Longhi-Santos, and J. R. Dittrich, “Regulation, trust and consumer preferences in Brazil’’s honey market: evidence from Paran state,” British Food Journal, Jan. 2026, doi: 10.1108/bfj-10-2025-1389.

[24] N. Kumar and Dr. A. Ahmad, “Transforming Rural Economies:,” Prayagraj Law Review, May 2025, doi: 10.61120/plr.2025.v3141-56.

[25] M. Assif, W. Kennedy, and I. Saniee, “Fair Allocation in Crowd-Sourced Systems,” Games, May 2023, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2305.12756.

[26] V. S. Bogolyubova, “The Compound Impact of Network Effects, Critical Mass, and Standartization on Competition in the Operating System Market,” Journal of Modern Competition, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.37791/2687-0657-2022-16-6-19-42.

[27] N. Jaapar, “Halal Branding and Trust-Building: Lessons from Nestl Malaysias Crisis Management and Community Engagement,” Journal of Halal Science and Management Research, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.24191/jhsmr.v1i1.8994.

[28] Isnawati, R. Setiawan, and Lindayani, “Mediating Role of Brand Perceived Quality in The Effect of Halal Label and Certification on Purchase Intention,” Golden Ratio of Marketing and Applied Psychology of Business, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.52970/grmapb.v6i1.1503.

[29] D. Herawatie, N. Siswanto, and E. Widodo, “A bibliometric analysis of multi-homing in multi-sided platforms and markets: Trends, influences, and research topics,” EPJ Web of Conferences, 2025, doi: 10.1051/epjconf/202534401054.

[30] G. Lin and R. Ren, “Pricing strategy for cross-market two-sided platforms based on joint membership system,” Theoretical and Natural Science, May 2024, doi: 10.54254/2753-8818/36/20240524.

[31] N. U. Qinvi, N. L. Hsb, I. B. Nusantara, and J. University, “Challenges in Competition Law Enforcement Against Data Monopoly in Indonesia’’s Digital Economy,” Justice Law Review, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.64317/jlr.v1i2.21.

[32] O. R, L. J, W. M, P. A, S. M, and N. K, “Artificial Intelligence-Empowered Radiology-Current Status and Critical Review.,” Jan. 2025, doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15030282.