Systematic Review of the Paleo Diet

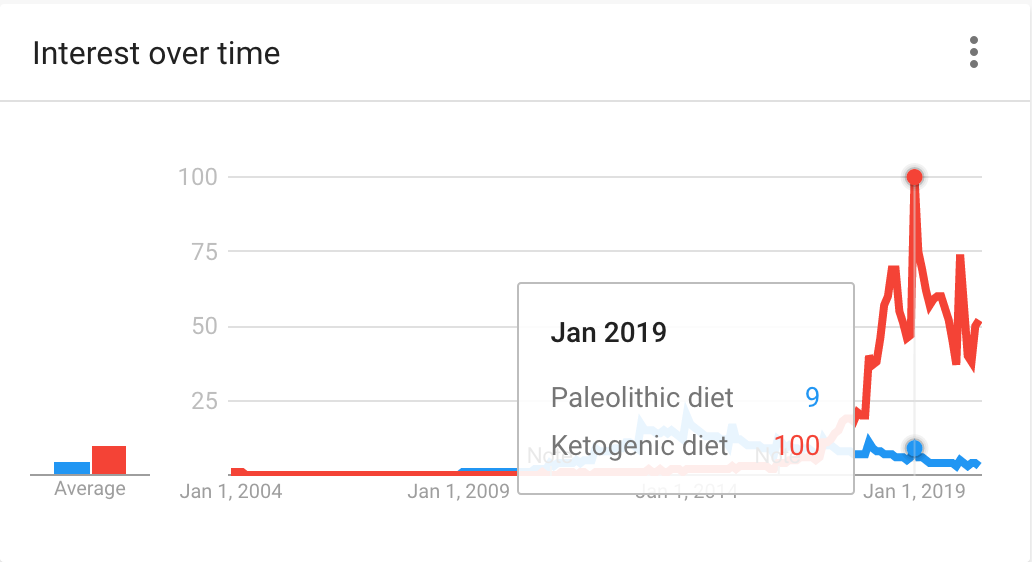

The Paleo Diet has gone down in popularity over the years, while other diets like the keto diet or carnivore diet have risen. However, popularity has never been a good index of whether something is safe, feasible, and effective. Although fewer people may be on a Paleo Diet, researchers have continued to study it because of the potential health benefits it may have to offer. The Effect of the Paleolithic Diet vs. Healthy Diets on Glucose and Insulin Homeostasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials is a systematic review and meta-analysis was recently published which investigated whether a Paleo Diet was effective in helping to manage glucose and insulin homeostasis. The researchers sought randomized controlled trials where the Paleo Diet was compared head to head to other control diets, thus they wished to see whether the Paleo Diet had a superior effect on metabolic outcomes relative to other diets.

A systematic review and meta-analysis was recently published [1] which investigated whether a paleo diet was effective in helping to manage glucose and insulin homeostasis. The researchers sought randomized controlled trials where the paleo diet was compared head to head to other control diets, thus they wished to see whether the paleo diet had a superior effect on metabolic outcomes relative to other diets.

Such an investigation makes sense given that most organizations that release guidelines on managing metabolic diseases such as the American Diabetes Association often recommend healthy eating patterns that are higher in protein, and lower in refined carbohydrates and highly processed foods [2].

Given that the paleo diet is a broad framework that promotes eating whole and nutritious foods [3], and mimicking certain principles from the diets of hunter-gatherer societies, which often result in high intake of fiber and protein, and low intakes of highly refined foods that are often high on the glycemic index, it is of interest to researchers who study interventions for managing metabolic disorders.

The researchers of this systematic review of the Paleo Diet and meta-analysis conducted a large-scale search of the published literature and sought randomized controlled trials that compared the paleolithic diet to some sort of control. The primary outcomes the researchers were interested in were post-intervention fasting glucose, insulin levels, HbA1c values, and HOMA-IR index, which are all typically monitored in individuals with metabolic diseases/disorders.

Systematic Review of the Paleo Diet: Results

After going through 110 papers and carefully screening them to see if they met the authors inclusion criteria, the authors included five papers in their overall systematic review. These included studies were published between 2006 and 2016.

There were a total of 96 participants from all four studies, with an average age that ranged from 52 years to 66 years. Most of the participants were also Caucasian and many lived in European nations. These studies often used paleo diets that were on average 25% higher in protein, higher in fat intake, higher in fiber intake, and lower in carbohydrate intake, when compared to the control diets used. On average, the individuals that were randomized to the paleo diet group also consumed fewer calories than those randomized to the control. Most of these studies lasted from two to twelve weeks.

After critically appraising the studies and pooling the effects from each study, the authors found that the paleo diet failed to result in statistically significant improvements for any of the primary outcomes of interest.

Interpretation

However, there is a giant caveat. Statistical significance is a very confusing phrase because it often gives the impression that if a result if not statistically significant, it’s tiny and meaningless [4,5]. This is not a reflection of reality. A result can fail to be statistically significant if the overall effect of an intervention is very small or if the study had too few participants. Suppose a treatment had a large effect, but not that many participants, it is possible that this result would not be statistically significant because the impreciseness of the result would make it “statistically insignificant”. This is often why many researchers emphasize that statistical significance is not the same as clinical significance and that drawing conclusions based on statistical significance is problematic when not considering the actual magnitude of the effect and its impreciseness.

In this case, the meta-analysis of the four studies showed that the paleo diet improved all the primary outcomes when compared to the control diet, however, the overall result was quite imprecise, which means it will typically fail to achieve statistical significance. This makes sense given that so few studies met the authors’ inclusion criteria and so few participants were in the included studies (N = 96).

Statistical significance is a highly controversial topic in statistics and research, dating back to at least the 1930s [6], however, despite statisticians warning against mindless use and interpretation, many authors fall victim to fallacies surrounding it, such as mistaking absence of evidence for evidence of absence [7]. In this case, the authors concluded with the latter, that there was “no effect”. This is not correct, because simply looking at the displayed graphs (shown below) show that the effect leans towards a paleo diet improving the outcomes, but the effect is imprecise, and because it is imprecise and not narrow (a hallmark of precise results), it failed to achieve statistical significance.

However, what the results suggest are that the paleo diet does indeed improve the preregistered outcomes chosen by the authors (post-intervention fasting glucose, insulin levels, HbA1c values, and HOMA-IR index), but that because there were so few participants and so few studies [8], the results are highly variable and more research will be needed.

Despite this study showing much promise for the paleo diet as an intervention to help manage metabolic syndromes/disorders, there were some problems with the meta-analysis and limitations. Although the composition of the paleo diets was very consistent between trials, this could not be said about the control diets which vastly differed. Furthermore, because the individuals that were randomized to the paleo diet group, on average, ate fewer calories than those on the control diet group, it is hard to parse the components of variance of the effect, was it the different foods that helped contribute substantially to these effects, or was it the lower energy intake? Results from much of the nutrition literature in the past has often suggested the latter [9], however, there may be more too metabolic homeostasis than simply reducing energy intake, which is no doubt a large contributor.

Another limitation is that the trials were quite short, with the longest trial only being 12 weeks and the shortest being 2 weeks. This may not be enough time to notice long-term trends when going on a paleo diet, and even, potential side effects. Furthermore, the very low number of studies [8] and participants makes the study results imprecise. Longer, and larger trials need to be conducted in order to derive a reasonable estimate of how effective the paleo diet is in affecting important biomarkers related to glycemic disorders.

References

• Jamka M, Kulczyński B, Juruć A, Gramza-Michałowska A, Stokes CS, Walkowiak J. The Effect of the Paleolithic Diet vs. Healthy Diets on Glucose and Insulin Homeostasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Med. 2020;9: 296. doi:10/gg278m

• Association AD. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42: S90–S102. doi:10/gfsxjp

• Challa HJ, Bandlamudi M, Uppaluri KR. Paleolithic Diet. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482457/

• Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. Am Stat. 2016;70: 129–133. doi:10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108

• Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA. Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05.” Am Stat. 2019;73: 1–19. doi:10.1080/00031305.2019.1583913

• Tyler RW. What is statistical significance? Educ Res Bull. 1931;10: 115–142.

• Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311: 485. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7003.485

• Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How Many Studies Do You Need?: A Primer on Statistical Power for Meta-Analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2010;35: 215–247. doi:10/bzk3gg

• Guyenet S. The Hungry Brain: Outsmarting the Instincts That Make Us Overeat. Ebury Publishing; 2017.