Is Low Stomach Acid Bad For Your Health?

Is Low Stomach Acid Bad For Your Health?

If you have ever watched television during the weeknight evening hours or had your regular radio programming interrupted by some messages from the sponsors, it is likely that you have been inundated with a slew of advertisements for antacids and acid-suppressing drugs, including the “purple pill” (Nexium), Prilosec, Prevacid, Pepcid AC, Zantac, and numerous other medications that lower stomach acid.

Understandably, you may be under the impression that the symptoms of heartburn, indigestion, and gastrointestinal acid reflux disease (GERD) are caused by too much stomach acid. As acid-suppressing drugs are among the most commonly used prescription and over-the-counter medications, the pharmaceutical companies are banking on acceptance of the idea that stomach acid is something that needs to be kept in check.

However, in reality, stomach acid is necessary for digestion to work properly and it is not something to be feared! It is much more likely that your symptoms are being caused by low stomach acid, instead of an overproduction of stomach acid.

Why Stomach Acid is Important

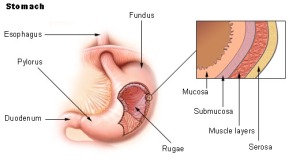

In the infinite wisdom of the human body, the stomach was designed to produce the acid that is necessary for the proper digestion of food. When functioning properly, the parietal cells of the stomach secrete hydrochloric acid that brings the stomach pH to a range of approximately 1.5 to 3.0. This is strong enough of an acid that if it were to be dropped on a piece of wood, it would burn a hole through the wood. The inner lining of the stomach is protected from its own acid by a thick layer of mucous and epithelial cells that produce a bicarbonate solution to neutralize the acid.

Stomach acid has several important roles including:

- Breakdown of proteins into a form that they can be digested (called proteolysis).

-

Activation of the enzyme pepsin, which is responsible for protein digestion.

-

Inhibition of the growth of microorganisms that enter the body through food to prevent infection.

- Proper absorption of many minerals, such as calcium, magnesium, zinc, and manganese.

-

Participation in triggering gastric emptying, or signaling the body when the food (referred to as chyme) is ready to leave the stomach and move into the small intestine for continued digestion.

When the digestive system is functioning normally, food travels down the esophagus to the stomach. The stomach works to ensure adequate mechanical digestion (by churning of the stomach) and production of stomach acid until the chyme is brought to the proper pH level to optimize the breakdown of proteins. As the normal digestive process continues, the valve at the lower end of the stomach, the pyloric sphincter, is triggered to open and release the chyme into the small intestine.

Opening of the pyloric sphincter is controlled by many complex neural, hormonal, and enteric factors, but the correct pH level in the stomach does play a role in gastric emptying. The pH level of the chyme entering the small intestine, as well as distension of the stomach and small intestine, triggers the release of pancreatic enzymes (to continue with the digestive process) and sodium bicarbonate (to neutralize the chyme to prevent burning of the small intestine).

What Happens When Stomach Acid is Too Low

When stomach acid production is low, dysfunction throughout the digestive system can occur, leading to numerous symptoms and disease processes. The body’s preference is to keep the chyme in the stomach until it has been broken down into small particles. When stomach acid production is low, gastric emptying may be slowed, leading the chyme to sit in the stomach for a longer period of time without the nutrients being broken down properly. At the same time, the low stomach acid promotes an environment that is more friendly to the growth of microorganisms, which are fed by the carbohydrates that become fermented from improper digestion. Eventually, excessive pressure from the bacterial overgrowth and maldigested food results.

The build-up of excessive pressure in the upper gastrointestinal tract may result in the opening of the valve that sits at the top of the stomach, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Opening the LES allows release of the pressure into the esophagus and that is what commonly leads to the symptoms of heartburn and acid reflux. Even if your stomach isn’t producing enough acid, any amount of acid going into the esophagus will result in uncomfortable symptoms because the esophagus is not designed to handle stomach acid. Frequent opening of the LES toward the esophagus will contribute to a weakened valve that compounds the problem.

**Note: There are also other causes that contribute to a malfunctioning LES. Certain foods (e.g. hot peppers, citrus, tomatoes), drinks (caffeine, alcohol), overeating, overweight and obesity, pregnancy, hiatal hernia, and many medications (including NSAIDs, antibiotics, bronchodilators, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, antidepressants, anti-anxiety, and anticholinergics) are associated with a weakened LES.

Low stomach acid also contributes to digestive problems downstream from the stomach in the small intestine. If the stomach is not able to produce enough acid to bring the pH level to an optimal range, after a while, the stomach will still empty the chyme through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine. Because it is not at the proper pH, the chyme may not trigger the release of enough sodium bicarbonate, which can result in duodenal ulcers. The higher pH of the chyme also does not trigger the release of an adequate amount of pancreatic enzymes.

The small intestine is not able to break down the chyme properly and the large, undigested particles of food can begin to have a negative impact on the lining of the small intestine. The lining becomes more permeable and allows the undigested food particles to enter the bloodstream where your body’s immune system recognizes them as foreign invaders. This triggers a systemic immune response that can lead to food sensitivities, inflammation, and autoimmune disease. This phenomenon is known as a leaky gut syndrome.

Some undigested food particles may continue into the large intestine. This malabsorbed food can lead to a disruption of the normal gut flora. The large intestine may become inflamed and subject to a variety of conditions, such as constipation, diarrhea, or irritable bowel syndrome. The disruption of the normal gut flora also impacts your overall immune system and can lead to autoimmune conditions.

Prevalence and Symptoms of Low Stomach Acid

Low stomach acid is a common problem in developed nations. According to Jonathon Wright, MD (author of “Why Stomach Acid is Good for You“), approximately 90% of Americans produce too little stomach acid. He arrived at this conclusion after measuring the stomach pH of thousands of patients in his clinic. While conventional medical doctors sometimes measure esophageal pH levels in particularly difficult cases of acid reflux, they never measure stomach pH levels. As mentioned above, any amount of acid in the esophagus is abnormal and will cause symptoms.

Because low stomach acid has such a profound impact on overall health, symptoms may affect a variety of body systems and result in conditions that include:

- Heartburn

- GERD

- Indigestion and bloating

- Burping or gas after meals

- Excessive fullness or discomfort after meals

- Constipation and/or diarrhea

- Chronic intestinal infections

- Undigested food in stools

- Food allergies, intolerances, and sensitivities

- Acne

- Chronic fatigue

- Mineral and nutrient deficiencies (including iron and/or vitamin B12 deficiency)

- Dry skin or hair

- Weak or cracked nails

- Asthma

- Depression

- Osteoporosis

- Any autoimmune disease diagnosis

What to do About Low Stomach Acid

Covering up symptoms of heartburn, indigestion, and acid reflux by lowering stomach acid production through the use of acid-suppressing drugs, is not necessarily an effective or safe way to address the root causes of low stomach acid. Holistic treatment starts with focusing on the underlying factors that contribute to low stomach acid, including reducing stress, eliminating processed carbohydrates and sugars in the diet, discovering food sensitivities and allergies, healing a leaky gut, treating pathogenic gut infections, and addressing nutrient deficiencies, such as zinc and vitamin C.

For many people, digestive support supplements may also prove to be helpful. However, it is always best to seek the advice of a qualified practitioner before taking such supplements, as they are not right for everyone.

Have you suffered from low stomach acid? What solutions did you find to get to the root cause of your symptoms? Please leave me a comment and share your experience!

References

Wright, J. & Lenard, L. (2001). Why Stomach Acid is Good for You: Natural Relief from Heartburn, Indigestion, Reflux, and GERD. Lanham, Maryland: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

One Response

my small intestine was colonised by candida albicans. was given antibioticswhich also killed off friendly bacteria.i was still suffering from uncomfortable bloating which affected my breathing. i then researched my symptoms on line and found several articles regarding stomach acid with low ph levels.i mentioned my concern to gastrologist and broached the subject of low ph in stomach but she spoke over me and did not offer explanation.frustrated at not being listened to,i went back on line and searched for remedies.i read article on apple cider vinegar which i purchased and started to take recomended dosage prior to meals. within one week my bloating had subsided and my bowel movements became more regular.now i only take acv in capsule form two or three times a week. my last ct scan showed small intestine back to normal. what didnt help was my doctor prescribed omneprazole when symptoms first appeared which lowered ph even further. i am 74 yr old male.